When Lytton Strachey set out to write “Eminent Victorians” in 1918, he sought to enliven the stuffy Victorian conventions of biographical writing by portraying his subjects with warts and all. In his new book “Eminent Jews,” David Denby pays tribute to that iconic work by choosing a similar-sounding title.

This sly homage simultaneously serves as a kind of callback to Denby’s own 1996 bestseller, “Great Books,” about reading the literary canon of the Western world at Columbia University. But unlike his predecessor, Denby, a staff writer at the New Yorker and former film critic there and at New York magazine, seeks to celebrate, not denigrate, his subjects. And what a celebration it is!

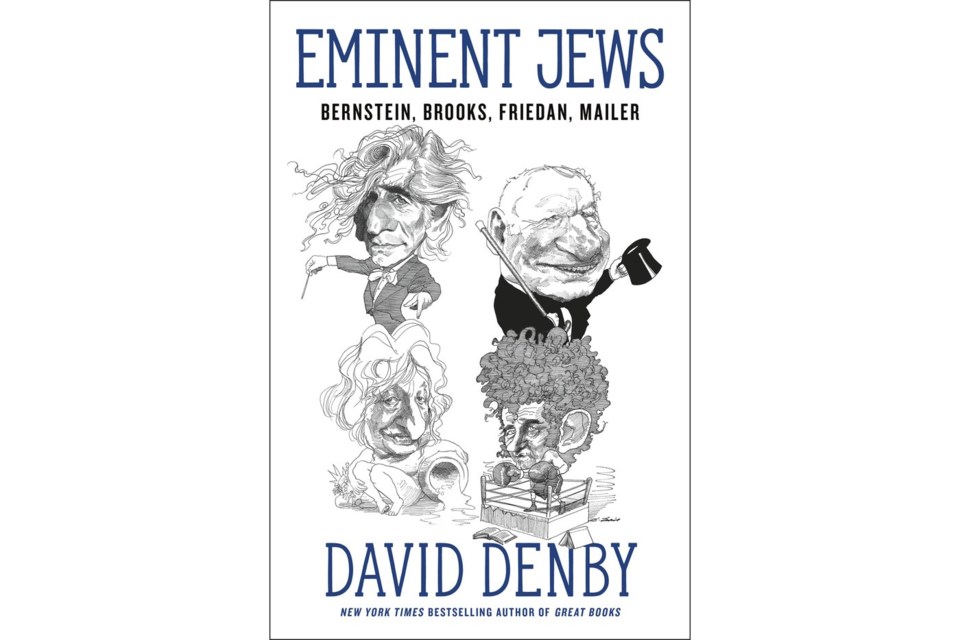

For his project Denby chose four of the most brilliant and consequential American Jews in the arts and letters after the Second World War — Mel Brooks, Betty Friedan, Norman Mailer and Leonard Bernstein — and analyzed their monumental, zeitgeist-changing achievements from the intimate perspective of a younger American Jew who came of age in a world that they in large part created.

Readers might reasonably ask why these four and not so many others whose lives burned brightly in the second half of the 20th century? Denby states his reasons clearly: Brooks transformed popular comedy, turning it into “a celebration of the body and an assault on death.” Friedan kicked off second-wave feminism, teaching women “to dismiss humiliation (and) confront anger.” Mailer created new forms of American prose and virtually invented “the bad Jewish boy.” And Bernstein wrote Broadway shows, popularized classical music and became one of the great conductors of the 20th century.

Though his overall tone is triumphal, Denby does not shy away from portraying their dark sides: Brooks’ need to dominate any room of writers; Bernstein’s sexual dalliances and later in life, his crude public behavior; Mailer’s promiscuity and the stabbing of his second wife; and Frieden’s mutually abusive marriage and difficulty sharing the spotlight with other feminist leaders.

At times, though, the book drags. Denby has clearly done so much research and is so besotted with his subjects that he is loath to leave anything out — though it is not hard to see why. One anecdote is juicier than the next, the literary equivalent of those lavish spreads at the Jewish resorts in the Catskills of yore where Brooks got his start and whose menus Denby lovingly recalls: chilled schav (sorrel soup) with sliced egg, boiled yearling fowl in a pot, and Vienna almond crescent.

___

AP book reviews:

Ann Levin, The Associated Press