The shaking started just after 9 a.m., rumbling through the wilderness about 130 kilometres northwest of Fort St. John, С����Ƶ

The Nov. 11 seismic event first registered as a , enough to send a Petronas crew fracking for gas into an emergency shutdown.

They “immediately suspended operations for 24 hours to allow for the built-up energy to dissipate,” said the С����Ƶ Oil and Gas Commission in an email.

The next evening, another magnitude 3.3 event hit, and four days after that, a 4.6 a kilometre to the south.

In the week since, seismologists have scrambled to check the numbers.

The earliest seismic data came from a network of 160 seismographs run by the . But in the Fort St. John area, coverage is sparse, said Honn Kao, seismologist with the Geologic Survey of Canada who heads the federal government's Induced Seismicity Research Project.

As the days passed, Kao started receiving numbers from other seismograph networks run by the С����Ƶ Oil and Gas Commission, several universities, and Petronas, which had its own instruments on site.

Instead of occurring at 8.2 and five kilometres below the surface, the two biggest quakes were found to have struck at a depth of around two kilometres in the Montney Formation — exactly where Petronas had been fracking.

“[The earthquakes] are very likely to be induced,” said the seismologist. “They occurred during active hydraulic fracturing and the location is very close to the injection sites.”

To date, human-caused earthquakes in С����Ƶ have been minor. When Kao and his team re-calibrated their calculations for the shallower depth, they downgrading the earthquakes’ magnitude to between 4 and 4.2. The С����Ƶ Oil and Gas Commission, meanwhile, said there was no “concern for public safety,” that the company followed best practices and that operations in the area are expected to continue until Nov. 25.

But Kao says there remain big open questions, and some scientists are still asking themselves, could humans trigger a major earthquake in С����Ƶ?

How do humans trigger earthquakes?

Most earthquakes occur along the margins of tectonic plates and fractures known as fault lines. When oceanic and continental plates collide, they rub, shift and slip past one another, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process.

On the surface, we feel that as an earthquake. At sea, a sudden displacement of the water column could trigger a tsunami.

But not all earthquakes are the result of natural processes. One that reviewed 730 anthropogenic projects thought to have induced earthquakes found mining was the most common seismic trigger, often due to collapsed material setting off shaking.

The most powerful human-triggered earthquake is thought to be the 2008 , which at magnitude 7.9, killed nearly 90,000 people. Scientists believe the earthquake's origins go back to 2015, when the Zipingpu Reservoir impounded 320 million tonnes of water. The water’s weight is thought to have pushed down on the Longmen Shan fault line, hastening the earthquake’s arrival by up to hundreds of years.

Water has been shown to set off earthquakes when forced underground as well.

In Switzerland, a magnitude 3.4 earthquake was triggered in Basel when water was injected underground into a . The 2006 event was followed by more than 200 earthquakes before the project was terminated in 2009.

The first documented case of human-caused earthquakes dates back to the 1960s, when a deep well was drilled into to dispose of contaminated waste water. By the end of the decade, more than 700 earthquakes had been recorded in the region, most with an epicentre within eight kilometres of the well.

Then came the hydraulic fracturing industry, which in recent decades has brought vast wealth to oil and gas companies across the U.S. and Canada.

Also known as fracking, the extraction technique blasts pressurized liquid underground to fracture bedrock formations laced with hydrocarbons. Particles like sand hold open the cracks, allowing natural gas and petroleum to pass through to the surface where it can be collected, processed and burned.

But the footprint of such extraction processes is not just felt through the planet’s shifting climate. Underground, the injected fluid raises the pressure in the cracks, fissures and the pores between sand and rock. Over years of extraction, that of underground formations, eventually coming into contact and lubricating a seismic fault.

“You make the fault easier to slip,” Kao said.

Fracked and shaken

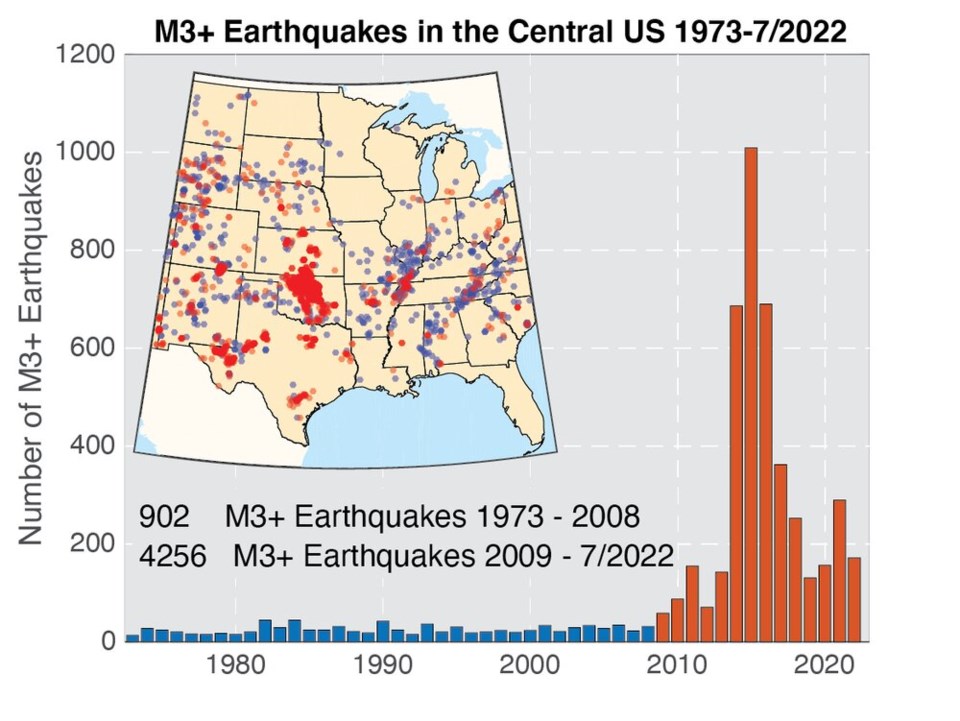

In the central United States, where fracking and wastewater injection from the oil and gas industry have expanded widely over the past decades, the number of earthquakes has increased dramatically.

According to the , the region experienced an average of 25 earthquakes of magnitude 3 and larger between 1973 and 2008. In 2009, that number more than doubled, and by 2015, more than 1,000 earthquakes M3 or larger hit the central U.S. In 2016, a magnitude 5.8 hit the Pawnee Nation, injuring a man as he tried to protect his child from falling bricks.

Canada’s oil and gas operations have not been spared. One of the largest human-induced earthquakes was in 2016, when a magnitude 4.8 quake hit Fox Creek, Alta. The shaking, thought to be set off by a Repsol Oil & Gas fracking operation, was so strong it was felt 280 kilometres away, CС����Ƶ News reported at the time.

“We noticed that one of the biggest events actually occurred about two weeks after the whole injection was completed,” said Kao.

In a follow-up study, his team found the fluids had reached a preexisting fault, setting off the earthquake. But the science is complicated and changes with local geology.

“The earthquake migration pattern is so different from all the others — and still linked back to injection of fluids, but in a very complicated way,” Kao said.

Erik Eberhardt, University of British Columbia professor of geological engineering, says his preliminary research suggests human-triggered earthquakes have an upper limit.

“We’re talking about in general,” he said. “But can we say it’s conclusive and it applies to everything? No. There’s no such thing as zero per cent.”

How risky are fracked earthquakes?

The complicated links between earthquakes and fracking come down to local geology and how much fracking occurs over time.

First, said Kao, you need to have some sort of seismic risk. If you conduct a high concentration of fracking operations close to an area that's already seismically active, say near С����Ƶ’s coast, you raise the risk of a man-made earthquake.

Conversely, if you pump water into the ground in Saskatchewan, where the risk of earthquakes is relatively low, there’s a lower risk of setting off an earthquake.

As Kao put it, imagine you have a loaded gun. The trigger is the fluid injected from fracking or wastewater disposal. The loaded bullet is the tectonic strain rate, priming the Earth to rumble. If you don't have that seismic risk, it doesn't matter how many times you pull the trigger, it's not going to fire anything.

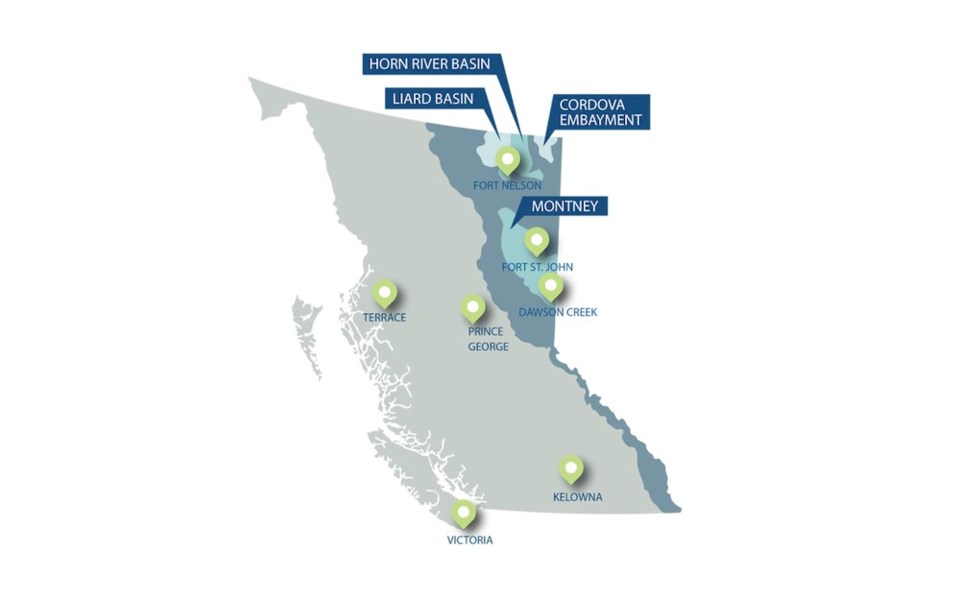

Things get complicated at the spaces in between, places like Fort St. John and the rest of northeastern С����Ƶ, major centres for fracking operations that sit on the edge of С����Ƶ's mountainous terrain, a place with some natural seismic risk.

In an email, the С����Ƶ Oil and Gas Commission said the area where these wells have been drilled is part of a “disturbed belt” with “a complicated structural history.”

“Faults are present in the area, which may be reactivated during injection activities,” wrote a commission spokesperson.

Kao says roughly one per cent of earthquakes in Canada have been linked to human activity; a number that climbs to two per cent in the United States, according to the USGS. Most are never felt and at no point has one event exceeded magnitude 5, said Kao.

That doesn’t mean there couldn’t be a large earthquake set off by human activity in the future. According to the Gutenberg-Richter law of seismology, the more small earthquakes there are over time, the more likely big ones will occur at some point down the road.

Regulatory action on the part of organizations like the С����Ƶ Oil and Gas Commission are meant to lower those risks. In Oklahoma, earthquakes bigger than magnitude 3 have dropped off significantly in recent years after fracking was dialled back (their frequency still remains substantially higher than before the fracking boom).

Kao says that if fracking is the kind of economic activity society decides can’t be avoided, then a regulatory framework is the best way to safeguard public safety. That means being able to shut down operations quickly and avoiding fracking in places at high risk of induced earthquakes.

That risk could increase in the coming years as subterranean fluid from hydraulic fracturing and wastewater injection are joined by the emerging practice of burying liquefied carbon captured from smokestacks or the atmosphere.

Scientists can help model how injecting fluid into the ground will affect the risk of seismic activity, but ultimately, said Kao, it will be up to government, the regulator, industry and local communities to decide what they’re comfortable with.

Are November’s earthquakes a sign the Peace region is seismically primed enough for fracking to trigger a major earthquake?

That's the most important question and a subject of intense research, said the seismologist.

“The Fort St. John area is not the highest region where you expect to have tectonic strain, but it is still there,” Kao said.

“What we are really trying to figure out is whether or not you do have a loaded bullet in the system.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated fracking operations in the area near the recent seismic activity are expected to continue Nov. 25. In fact, the operations are expected to continue until Nov. 25.