С����Ƶ’s largest health authority is warning residents of Metro Vancouver to prepare for a smoky summer.

With close to 300 wildfires burning across the province, smoke has been billowing north and east, blanketing 23 regions of the province in air quality warnings from the southern Interior to the Peace River.

“As we anticipate our region will be impacted by wildfire smoke, I encourage those at higher risk to plan ahead, including identifying a place to go that has cleaner air,” says Dr. Ingrid Tyler, Fraser Health’s executive medical director of population and public health and a medical health officer.

Meteorologists say a change in wind, though not on the immediate horizon, could quickly envelop the Lower Mainland and Fraser Valley in thick smoke.

“We do know with reasonable accuracy that we don’t expect substantial smoke in the next 72 hours,” says Arvind Saraswat, senior project engineer with Metro Vancouver’s air quality and climate group.

“It’s hard to tell what’s going to happen after the weekend.”

Lisa Erven, a meteorologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, says her models predict westerly winds will continue to push smoke across the Prairies for the next 10 days. That is, barring any new fires.

“There are fires burning to all sides of us — the Yukon, Interior С����Ƶ and south of the border,” she says. “It wouldn’t take much for smoke to be transported to the coast.”

SMOKE A BIG BLIND SPOT

Worldwide, air pollution kills roughly seven million people, according to the .

In places like British Columbia, wildfire smoke is a major contributor to the more than who die prematurely across Canada every year due to air pollution, says Michael Mehta, who researches environmental and health risks at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops.

Mehta says the increasing duration and magnitude of wildfire smoke in С����Ƶ is overwhelming researchers’ ability to understand the short- and long-term scale of smoke’s impacts on human health.

Like death due to heat illness, it’s not always clear whether a person dies because of a pre-existing condition, long-term exposure to fine particulate matter or a spike in smoke exposure.

On the low end, smoke can trigger lung and eye irritation, a runny nose, headache or a sore throat and mild cough. Experts recommend seeking medical treatment immediately if those symptoms escalate to shortness of breath, a severe cough, dizziness, chest discomfort, heat palpitations or wheezing.

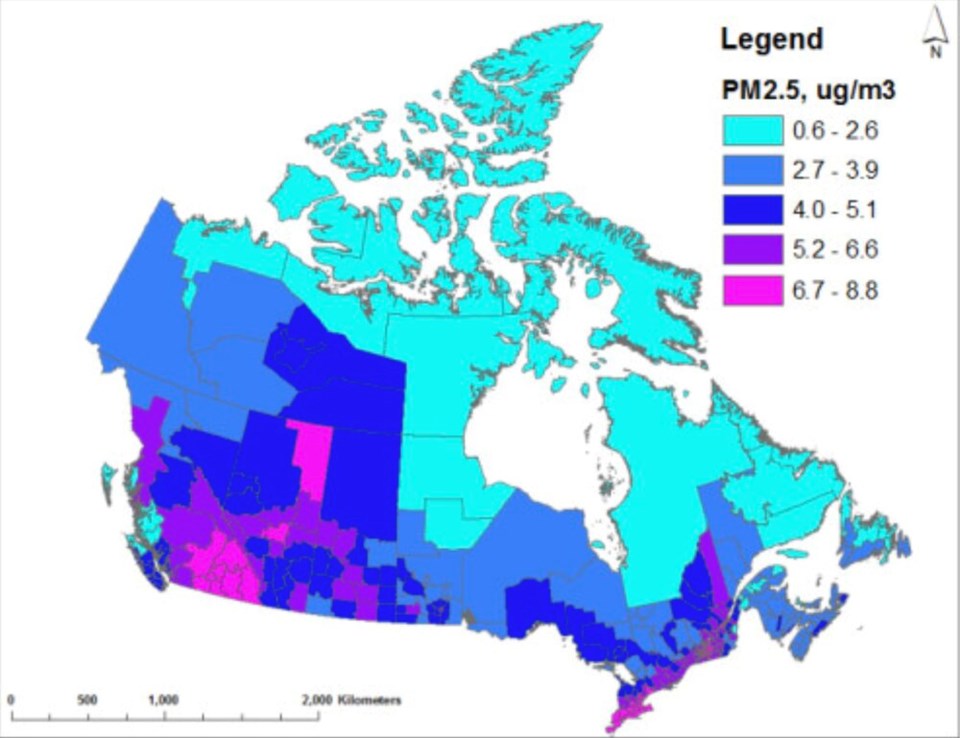

Three-year population-weighted average of daily fine particulate concentrations (PM2.5) across Canadian census divisions – 2015–2017 (includes air pollution from all sources). By Statistics Canada

Three-year population-weighted average of daily fine particulate concentrations (PM2.5) across Canadian census divisions – 2015–2017 (includes air pollution from all sources). By Statistics CanadaWhat researchers do know, says Mehta, is that you need to measure a problem — made worse every year by climate change — before experts can diagnose its impact on public health.

To fix that, Mehta has helped set up , a real-time air quality monitoring system across the province.

Mehta says he was spurred to act because the provincial government didn’t provide the kind of granular data that both researchers and everyday people need.

“We know smoke kills a lot more people than the fire,” he says. “There’s a really significant blindspot when it comes to air pollution.”

At a station west of Kamloops Tuesday, Purple Air recorded fine particulate readings of over 300 micrograms per cubic metre over one hour. That’s well over the provincial one-hour objective of 25 micrograms per cubic metre per hour, says Mehta.

“It’s very dangerous. Once you get over 150 micrograms [per cubic metre for 72 hours], in Beijing they call a red-alert day. The city is essentially shut down. There are limits on driving, kids are taken out of school,” he says.

“We’re having similar or higher levels of exposure.”

HOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF FROM SMOKE

There are ways to mitigate risk from wildfire smoke.

Fraser Health recommends the following to keep yourself safe from smoky air:

- Check your medications, especially rescue medications for breathing

- Keep windows and doors closed if possible without overheating

- Use a portable HEPA air cleaner

- Stay hydrated

- Reduce time spent outdoors and reduce strenuous activities, because breathing harder means inhaling more smoky air

Outside Mehta’s own home in Kamloops, the researcher has set up his own air quality instruments to see how much smoke is making it inside.

Mehta’s wife has asthma, and like children and older adults, those with pre-existing conditions are especially vulnerable to particulate matter from wildfire smoke.

Outside on Tuesday morning, Mehta says the Air Quality Index was hitting 156; inside, where he has a floor-mounted he bought off Amazon, that dropped to four.

“There’s virtually no smoke,” he says.

Mehta is plugged into the latest science on wildfire smoke. But for your average British Columbian, he says there should be a minimum standard for air filtration.

With climate change only darkening our summer skies with smoke, now is the time to make HEPA filters mandatory in every new build, he says.

In the meantime, Mehta says people need to take their health into their own hands: some people install HEPA filters in their furnaces; Mehta says others have found success in low-budget solutions, like strapping a HEPA filter to an .

“I’m just glad I have this filtration in my house,” he says. “My wife has asthma. Without it, she’d be in trouble.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story quoted Purple Air readings in parts per million per hour. These figures, in fact, are in micrograms per cubic metre per hour.